RECEIVABLES: You already know that receivables arise from a variety of claims against customers and others, and are generally classified as current or noncurrent based on expectations about the amount of time it will take to collect them. The majority of receivables are classified as trade receivables, which arise from the sale of products or services to customers. Such trade receivables are carried in the Accounts Receivable account. Nontrade receivables arise from other transactions and events, including advances to employees and utility company deposits.

CREDIT SALES: To one degree or another, many business transactions result in the extension of credit. Purchases of inventory and supplies will often be made on account. Likewise, sales to customers may directly (by the vendor offering credit) or indirectly (through a bank or credit card company) entail the extension of credit. While the availability of credit facilitates many business transactions, it is also costly. Credit providers must conduct investigations of credit worthiness, and monitor collection activities. In addition, the creditor must forego alternative uses of money while credit is extended. Occasionally, a creditor will get burned when the borrower refuses or is unable to pay. Depending on the nature of the credit relationship, some credit costs may be offset by interest charges. And, merchants frequently note that the availability of credit entices customers to make a purchase decision.

CREDIT CARDS: Banks and financial services companies have developed credit cards that are widely accepted by many merchants, and eliminate the necessity of those merchants maintaining separate credit departments. Popular examples include MasterCard, Visa, and American Express. These credit card companies earn money off of these cards by charging merchant fees (usually a formula-based percentage of sales) and assess interest and other charges against the users. Nevertheless, merchants tend to welcome their use because collection is virtually assured and very timely (oftentimes same day funding of the transaction is made by the credit card company). In addition, the added transaction cost is offset by a reduction in the internal costs associated with maintaining a credit department.

The accounting for credit card sales depends on the nature of the card. Some bank-card based transactions are essentially regarded as cash sales since funding is immediate. Assume that Bassam Abu Rayyan Company sold merchandise to a customer for $1,000. The customer paid with a bank card, and the bank charged a 2% fee. Bassam Abu Rayyan Company should record the following entry:

cash debit

service charges debit

sales credit

then

account receivable debit

sales credit

cash debit

service charges debit

account receivable credit

Notice that the entry to record the collection included a provision for the service charge. The estimated service charge could (or perhaps should) have been recorded at the time of the sale, but the exact amount might not have been known. Rather than recording an estimate, and adjusting it later, this illustration is based on the simpler approach of not recording the charge until collection occurs. This expedient approach is acceptable because the amounts involved are not very significant.

ACCOUNTING FOR UNCOLLECTIBLE RECEIVABLES

UNCOLLECTIBLE RECEIVABLES: Unfortunately, some sales on account may not be collected. Customers go broke, become unhappy and refuse to pay, or may generally lack the ethics to complete their half of the bargain. Of course, a company does have legal recourse to try to collect such accounts, but those often fail. As a result, it becomes necessary to establish an accounting process for measuring and reporting these uncollectible items. Uncollectible accounts are frequently called "bad debts."

DIRECT WRITE-OFF METHOD: A simple method to account for uncollectible accounts is the the direct write-off approach. Under this technique, a specific account receivable is removed from the accounting records at the time it is finally determined to be uncollectible. The appropriate entry for the direct write-off approach is as follows:

2-10-X7

Uncollectible Accounts Expense 500 debit

Accounts Receivable 500 credit

To record the write off of an uncollectible account from Jones

Notice that the preceding entry reduces the receivables balance for the item that is deemed uncollectible. The offsetting debit is to an expense account: Uncollectible Accounts Expense.

While the direct write-off method is simple, it is only acceptable in those cases where bad debts are immaterial in amount. In accounting, an item is deemed material if it is large enough to affect the judgment of an informed financial statement user. Accounting expediency sometimes permits "incorrect approaches" when the effect is not material. Recall the discussion of nonbank credit card charges above; there, the service charge expense was recorded subsequent to the sale, and it was suggested that the approach was lacking but acceptable given the small amounts involved. Again, materiality considerations permitted a departure from the best approach. But, what is material? It is a matter of judgment, relating only to the conclusion that the choice among alternatives really has very little bearing on the reported outcomes.

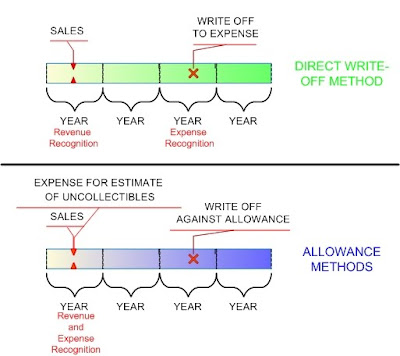

You must now consider why the direct write-off method is not to be used in those cases where bad debts are material; what is "wrong" with the method? One important accounting principle is the notion of matching. That is, costs related to the production of revenue are reported during the same time period as the related revenue (i.e., "matched"). With the direct write-off method, you can well understand that many accounting periods may come and go before an account is finally determined to be uncollectible and written off. As a result, revenues from credit sales are recognized in one period, but the costs of uncollectible accounts related to those sales are not recognized until another subsequent period (producing an unacceptable mismatch of revenues and expenses).

To compensate for this problem, accountants have developed "allowance methods" to account for uncollectible accounts. Importantly, an allowance method must be used except in those cases where bad debts are not material (and for tax purposes where tax rules often stipulate that a direct write-off approach is to be used). Allowance methods will result in the recording of an estimated bad debts expense in the same period as the related credit sales. As you will soon see, the actual write off in a subsequent period will generally not impact income.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES FOR UNCOLLECTIBLES

ALLOWANCE METHODS: Having established that an allowance method for uncollectibles is preferable (indeed, required in many cases), it is time to focus on the details. Let's begin with a consideration of the balance sheet. Suppose that Ito Company has total accounts receivable of $425,000 at the end of the year, and is in the process or preparing a balance sheet. Obviously, the $425,000 would be reported as a current asset. But, what if it is estimated that $25,500 of this amount may ultimately prove to be uncollectible? Thus, a more correct balance sheet presentation would appear as shown at right:

The total receivables are reported, along with an allowance account (which is a contra asset account) that reduces the receivables to the amount expected to be collected. This anticipated amount to be collected is often termed the "net realizable value."

DETERMINING THE ALLOWANCE ACCOUNT: In the preceding illustration, the $25,500 was simply given as part of the fact situation. But, how would such an amount actually be determined? If Ito Company's management knew which accounts were likely to not be collectible, they would have avoided selling to those customers in the first place. Instead, the $25,500 simply relates to the balance as a whole. It is likely based on past experience, but it is only an estimate. It could have been determined by one of the following techniques:

AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL RECEIVABLES: Some companies anticipate that a certain percentage of outstanding receivables will prove uncollectible. In Ito's case, maybe 6% ($425,000 X 6% = $25,500).

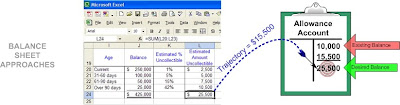

VIA AN AGING ANALYSIS: Other companies employ more sophisticated aging of accounts receivable analysis. They will stratify the receivables according to how long they have been outstanding (i.e., perform an aging), and apply alternative percentages to the different strata. Obviously, the older the account, the more likely it is to represent a bad account. Ito's aging may have appeared as follows:

Both the percentage of total receivables and the aging are termed "balance sheet approaches." In both cases, the allowance account is determined by an analysis of the outstanding accounts receivable on the balance sheet. Once the estimated amount for the allowance account is determined, a journal entry will be needed to bring the ledger into agreement. Assume that Ito's ledger revealed an Allowance for Uncollectible Accounts credit balance of $10,000 (prior to performing the above analysis). As a result of the analysis, it can be seen that a target balance of $25,500 is needed; necessitating the following adjusting entry:

Uncollectible Accounts Expense15,500 debit

Allow. for Uncollectible Accounts15,500 credit

You should carefully note two important points: (1) with balance sheet approaches, the amount of the entry is based upon the needed change in the account (i.e., to go from an existing balance to the balance sheet target amount), and (2) the debit is to an expense account, reflecting the added cost associated with the additional amount of anticipated bad debts.

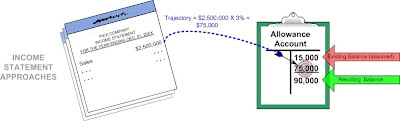

Rather than implement a balance sheet approach as above, some companies may follow a simpler income statement approach. With this equally acceptable allowance technique, an estimated percentage of sales (or credit sales) is simply debited to Uncollectible Accounts Expense and credited to the Allowance for Uncollectible Accounts each period. Importantly, this technique merely adds the estimated amount to the Allowance account. To illustrate, assume that Pick Company had sales during the year of $2,500,000, and it records estimated uncollectible accounts at a rate of 3% of total sales. Therefore, the appropriate entry to record bad debts cost is as follows:

Uncollectible Accounts Expense debit 75,000

Allow. for Uncollectible Accounts credit 75,000

To add 3% of sales to the allowance account ($2,500,000 X 3% = $75,000)

This entry would be the same even if there was already a balance in the allowance account. In other words, the income statement approach adds the calculated increment to the allowance, no matter how much may already be in the account from prior periods.

WRITING OFF UNCOLLECTIBLE ACCOUNTS: Now, we have seen how to record uncollectible accounts expense, and establish the related allowance. But, how do we write off an individual account that is determined to be uncollectible? This part is easy. The following entry would be needed to write off a specific account that is finally deemed uncollectible:

3-15-X3

Allow. for Uncollectible Accounts debit 5,000

Accounts Receivable credit 5,000

To record the write-off of an uncollectible account from Aziz

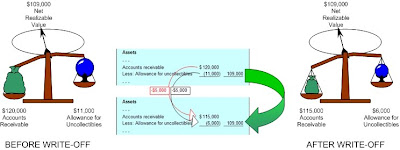

Notice that the entry reduces both the allowance account and the related receivable, and has no impact on the income statement. Further, consider that the write-off has no impact on the net realizable value of receivables, as shown by the following illustration of a $5,000 write-off:

COLLECTION OF AN ACCOUNT PREVIOUSLY WRITTEN OFF: On occasion, a company may collect an account that was previously written off. For example, a customer that was once in dire financial condition may recover, and unexpectedly pay an amount that was previously written off. The entry to record the recovery involves two steps: (1) a reversal of the entry that was made to write off the account, and (2) recording the cash collection on the account:

6-16-X6

Accounts Receivable 1,000

Allow. for Uncollectible Accounts 1,000

To reestablish an account previously written off via the reversal of the entry recorded at the time of write off

6-16-X6

Cash 1,000

Accounts Receivable 1,000

To record collection of account receivable

It may trouble you to see the allowance account being increased because of the above entries, but the general idea is that another as yet unidentified account may prove uncollectible (consistent with the overall estimates in use). If this does not eventually prove to be true, an adjustment of the overall estimation rates may eventually be indicated.

MATCHING ACHIEVED: Carefully consider that the allowance methods all result in the recording of estimated bad debts expense during the same time periods as the related credit sales. These approaches satisfy the desired matching of revenues and expenses.

MONITORING AND MANAGING ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE: A business must carefully monitor its accounts receivable. This chapter has devoted much attention to accounting for bad debts; but, don't forget that it is more important to try to avoid bad debts by carefully monitoring credit policies. A business should carefully consider the credit history of a potential credit customer, and be certain that good business practices are not abandoned in the zeal to make sales. It is customary to gather this information by getting a credit application from a customer, checking out credit references, obtaining reports from credit bureaus, and similar measures. Oftentimes, it becomes necessary to secure payment in advance or receive some other substantial guarantee such as a letter of credit from an independent bank. All of these steps are normal business practices, and no apologies are needed for making inquiries into the creditworthiness of potential customers. Many countries have very liberal laws that make it difficult to enforce collection on customers who decide not to pay or use "legal maneuvers" to escape their obligations. As a result, businesses must be very careful in selecting parties that are allowed trade credit in the normal course of business.

Equally important is to monitor the rate of collection. Many businesses have substantial dollars tied up in receivables, and corporate liquidity can be adversely impacted if receivables are not actively managed to insure timely collection. One ratio that is often monitored is the accounts receivable turnover ratio. That number reveals how many times a firm's receivables are converted to cash during the year. It is calculated as net credit sales divided by average net accounts receivable:

Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio = Net Credit Sales/Average Net Accounts Receivable

To illustrate these calculations, assume Shoztic Corporation had annual net credit sales of $3,000,000, beginning accounts receivable (net of uncollectibles) of $250,000, and ending accounts receivable (net of uncollectibles) of $350,000. Shoztic's average net accounts receivable is $300,000 (($250,000 + $350,000)/2), and the turnover ratio is "10":

10 = $3,000,000/$300,000

A closely related ratio is the "days outstanding" ratio. It reveals how many days sales are carried in the receivables category:

Days Outstanding = 365 Days/Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

For Shoztic, the days outstanding calculation is:

36.5 = 365/10

By themselves, these numbers mean little. But, when compared to industry trends and prior years, they will reveal important signals about how well receivables are being managed. In addition, the calculations may provide an "early warning" sign of potential problems in receivables management and rising bad debt risks. Analysts carefully monitor the days outstanding numbers for signs of weakening business conditions. One of the first signs of a business downturn is a delay in the payment cycle. These delays tend to have ripple effects; if a company has trouble collecting its receivables, it won't be long before it may have trouble paying its own obligations.

NOTES RECEIVABLE

NOTES RECEIVABLE: A written promise from a client or customer to pay a definite amount of money on a specific future date is called a note receivable. Such notes can arise from a variety of circumstances, not the least of which is when credit is extended to a new customer with no formal prior credit history. The lender uses the note to make the loan more formal and enforceable. Such notes typically bear interest charges. The maker of the note is the party promising to make payment, the payee is the party to whom payment will be made, the principal is the stated amount of the note, and the maturity date is the day the note will be due.

Interest is the charge imposed on the borrower of funds for the use of money. The specific amount of interest depends on the size, rate, and duration of the note. In mathematical form: Interest = Principal X Rate X Time. For example, a $1,000, 60-day note, bearing interest at 12% per year, would result in interest of $20 ($1,000 X 12% X 60/360). In this calculation, notice that the "time" was 60 days out of a 360 day year. Obviously, a year normally has 365 days, so the fraction could have been 60/365. But, for simplicity, it is not uncommon for the interest calculation to be based on a presumed 360-day year or 30-day month. This presumption probably has its roots in olden days before electronic calculators, as the resulting interest calculations are much easier with this assumption in place. But, with today's technology, there is little practical use for the 360 day year, except that it tends to benefit the creditor by producing a little higher interest amount -- caveat emptor (Latin for "let the buyer beware")! The following illustrations will preserve this archaic approach with the goal of producing nice round numbers that are easy to follow.

ACCOUNTING FOR NOTES RECEIVABLE: To illustrate the accounting for a note receivable, assume that Butchko initially sold $10,000 of merchandise on account to Hewlett. Hewlett later requested more time to pay, and agreed to give a formal three-month note bearing interest at 12% per year. The entry to record the conversion of the account receivable to a formal note is as follows:

6-1-X8

Notes Receivable 10,000

Accounts Receivable 10,000

To record conversion of an account receivable to a note receivable

When the note matures, Butchko's entry to record collection of the maturity value would appear as follows:

8-31-X8

Cash 10,300

Interest Income 300

Notes Receivable 10,000

To record collection of note receivable plus accrued interest of $300 ($10,000 X 12% X 90/360)

A DISHONORED NOTE: If Hewlett dishonored the note at maturity (i.e., refused to pay), then Butchko would prepare the following entry:

8-31-X8

Accounts Receivable 10,300

Interest Income 300

Notes Receivable 10,000

To record dishonor of note receivable plus accrued interest of $300 ($10,000 X 12% X 90/360)

The debit to Accounts Receivable in the above entry reflects the hope of eventually collecting all amounts due, including the interest, from the dishonoring party. If Butchko anticipated some difficulty in collecting the receivable, appropriate allowances would be established in a fashion similar to those illustrated earlier in the chapter.

NOTES AND ADJUSTING ENTRIES: In the above illustrations for Butchko, all of the activity occurred within the same accounting year. However, if Butchko had a June 30 accounting year end, then an adjustment would be needed to reflect accrued interest at year-end. The appropriate entries illustrate this important accrual concept:

Entry to set up note receivable:

6-1-X8

Notes Receivable 10,000

Accounts Receivable 10,000

To record conversion of an account receivable to a note receivable

Entry to accrue interest at June 30 year end:

6-30-X8

Interest Receivable 100

Interest Income 100

To record accrued interest at June 30 ($10,000 X 12% X 30/360 = $100)

Entry to record collection of note (including amounts previously accrued at June 30):

8-31-X8

Cash 10,300

Interest Income 200

Interest Receivable 100

Notes Receivable 10,000

To record collection of note receivable plus interest of $300 ($10,000 X 12% X 90/360); $100 of the total interest had been previously accrued

The following drawing should aid your understanding of these entries:

Selengkapnya →